Parel Silhouet – English

2019Through research into the pearl production process, Hiroi explored the relationship between people and nature, and created a work consisting of photographs, text, poetry, video and textile artworks expressing the Dutch global network that began in the 17th century, the darkness of colonialism and the brilliance of pearls. Following literature research on the history of pearls, fieldwork was conducted in Nagasaki, interviewing and photographing people working in the pearling industry about their prosperity and decline, living and working with the sea.

Concept, Research and Development: Kumi Hiroi Text, Tapestry, Silkscreen Print and Video: Kumi Hiroi Poem (Renga): Erik Akkermans and Kumi Hiroi Translation (JP to EN): Polly Barton Translation of the poem: Masafumi Kunimori Text editing (NL): Adinda Akkermans Proofreading: Yumiko Kunimori Photo: Hymmen & Hiroi © Kumi Hiroi Photography development: Fotolab Kiekie Tapestry development: Lotte van Dijk in TextielLab

Project director: Chitose Ochi, Supported by Nagasaki Holland Village, Sorisso Riso, Nagasaki Prefectural Museum, IMA gallery & amana.inc, Nagasaki Bus, Pearl industry Nagasaki, Dutch Creative Industry Fund and Dutch Embassy in Tokyo.

PEARLS AND THE DUTCH GOLDEN AGE

When you hear the phrase ‘Pearls and the Dutch

Golden Age’, what image comes to mind?

It’s likely that many will think of the painting by Johannes Vermeer, Het meisje met de parel [The Girl with

the Pearl Earring]. In Vermeer’s time, however, it was only the wealthy who

could afford to wear real pearls. It’s thus said that what the young girl in

the painting is wearing is in fact not a real pearl, but rather a glass earring

whose inside has been stained to give it the appearance of a pearl.

The

picture De burgemeester van Delft en zijn

dochter [The Burgomaster of Delft and his Daughter] features real pearls.

The work by Jan Steen was acquired by Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum in 2004 for 11.9

million Euros. It shows four people positioned outside the residence of the

Delft mayor’s residence. Seated centrally is a wealthy man of around forty, and

standing on his left is a young girl, apparently his daughter. To the right of

the man are an impoverished woman and her son. The girl on the left wearing the

pearl necklace forms a clear contrast with the beggarwoman on the right.

Jan Steen left behind many paintings depicting

everyday scenes of 17th century life. These often reflect the darker aspects of

the society, depicting the lives of the common people as they sit around a

candlelit table. Frans

Grijzenhout, an expert on Dutch Golden Age painting, has much to say on

the topic of Jan Steen’s painting. An art history lecturer at Amsterdam

University, Grijzenhout is also the presenter of a television programme unearthing

the secrets lying behind Golden Age masterpieces. Plentiful research led him to

the discovery that the central figure in The

Burgomaster of Delft and his Daughter wasn’t in fact a Burgomaster—rather,

the man sitting outside the Mayor’s residence was in fact a corn merchant.

About the charm of Jan Steen’s paintings, Grijzenhout says: ‘They’re funny and

seem to speak directly to the viewer. People can see themselves in them. The canvases

present “normal” scenes from Golden Age life.’

‘The man in this picture is wearing a black outfit,

in a black, silken fabric. From that, we can deduce he is a wealthy merchant. On

his left index finger he wears a signet ring, used to seal wax on letters. His

daughter is wearing the costume often seen on girls of up to 17 years of age. Her

skirt is rolled up and held in place with pins, so we can clearly see her

expensive underskirt and elegant shoes. And she’s wearing pearls. Her father is

clearly from the affluent class. In the Golden Age, affluent parents often wore

black, but the real extent of their wealth was shown in the pearl earrings, necklaces,

and bracelets worn by their children.’

Grijzenhout estimates that the necklace the girl is

wearing would have cost between 50 to 150 guilders. When we consider that the

annual salary of an unskilled tradesman at the time was 300 guilders, and that

of a skilled tradesman 400 guilders, it shows us just how costly pearls were.

In the Golden Age, society was clearly divided into classes: an upper class

made up of regenten (the rulers of the country and cities and heads of

organisations) and wealthy merchants; a middle class made up of shopkeepers and

artisans; and a lower class of people with limited resources. The classes were

divided according to their participation in manual labour, and how much capital

they owned. The upper class did not partake in manual labour. The middle class

of shopkeepers and craftsmen were involved with manual labour, but owned some capital

in the form of stock and raw materials. Those from the lower class only had

their labour to sell.

Frans Grijzenhout: ‘De kleding van de bedelares is eenvoudig, maar het bont op haar muts wijst er mogelijk op dat ze betere dagen heeft gekend. In die tijd is een muts met een bontrandje typisch Duitse klederdracht. In de 17de eeuw kwamen veel arme Duitse migranten naar de rijke Nederlandse republiek in de hoop op een beter bestaan. De vaas met bloemen staat vreemd genoeg niet binnen,maar buiten in het venster. Ook in de Gouden Eeuw is dat apart, Jan Steen moet er dus iets mee bedoeld hebben. Een boeket staat in het algemeen symbool voor de kwetsbaarheid van het leven. In dit geval verwijst het mogelijk ook naar de dood van de echtgenote van de afgebeelde man.’

Grijzenhout continues: ‘The beggar woman’s clothes are plain, but the fur

on her hat may indicate that she has seen better days. At that time, a hat with

a fur trim was typical German attire. In the 17th century, many poor German

migrants arrived in the rich Dutch Republic in the hope of a better life.

Strangely enough, the vase with flowers is placed not inside, but outside the

window. This is unusual, so Jan Steen doubtless meant something by it. A

bouquet of flowers generally symbolizes the fragility of life. In this case, it

may allude to the death of the husband's wife.’

So the

painting depicts a wealthy corn trader who has lost his partner, a well-dressed

young girl born into an affluent household, and begging immigrants. The scene

is one that one might see in the Netherlands in the present day also, albeit

with the characters wearing different clothes. The ‘normal’ Golden Age life

depicted by Jan Steen continues to capture the hearts of ‘normal’ people into

our current age.

The picture De burgemeester van Delft en zijn dochter [The Burgomaster of Delft and his Daughter] features real pearls. The work by Jan Steen was acquired by Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum in 2004 for 11.9 million Euros. It shows four people positioned outside the residence of the Delft mayor’s residence. Seated centrally is a wealthy man of around forty, and standing on his left is a young girl, apparently his daughter. To the right of the man are an impoverished woman and her son. The girl on the left wearing the pearl necklace forms a clear contrast with the beggarwoman on the right.

Jan Steen left behind many paintings depicting

everyday scenes of 17th century life. These often reflect the darker aspects of

the society, depicting the lives of the common people as they sit around a

candlelit table. Frans

Grijzenhout, an expert on Dutch Golden Age painting, has much to say on

the topic of Jan Steen’s painting. An art history lecturer at Amsterdam

University, Grijzenhout is also the presenter of a television programme unearthing

the secrets lying behind Golden Age masterpieces. Plentiful research led him to

the discovery that the central figure in The

Burgomaster of Delft and his Daughter wasn’t in fact a Burgomaster—rather,

the man sitting outside the Mayor’s residence was in fact a corn merchant.

About the charm of Jan Steen’s paintings, Grijzenhout says: ‘They’re funny and

seem to speak directly to the viewer. People can see themselves in them. The canvases

present “normal” scenes from Golden Age life.’

‘The man in this picture is wearing a black outfit,

in a black, silken fabric. From that, we can deduce he is a wealthy merchant. On

his left index finger he wears a signet ring, used to seal wax on letters. His

daughter is wearing the costume often seen on girls of up to 17 years of age. Her

skirt is rolled up and held in place with pins, so we can clearly see her

expensive underskirt and elegant shoes. And she’s wearing pearls. Her father is

clearly from the affluent class. In the Golden Age, affluent parents often wore

black, but the real extent of their wealth was shown in the pearl earrings, necklaces,

and bracelets worn by their children.’

Grijzenhout estimates that the necklace the girl is wearing would have cost between 50 to 150 guilders. When we consider that the annual salary of an unskilled tradesman at the time was 300 guilders, and that of a skilled tradesman 400 guilders, it shows us just how costly pearls were. In the Golden Age, society was clearly divided into classes: an upper class made up of regenten (the rulers of the country and cities and heads of organisations) and wealthy merchants; a middle class made up of shopkeepers and artisans; and a lower class of people with limited resources. The classes were divided according to their participation in manual labour, and how much capital they owned. The upper class did not partake in manual labour. The middle class of shopkeepers and craftsmen were involved with manual labour, but owned some capital in the form of stock and raw materials. Those from the lower class only had their labour to sell.

Frans Grijzenhout: ‘De kleding van de bedelares is eenvoudig, maar het bont op haar muts wijst er mogelijk op dat ze betere dagen heeft gekend. In die tijd is een muts met een bontrandje typisch Duitse klederdracht. In de 17de eeuw kwamen veel arme Duitse migranten naar de rijke Nederlandse republiek in de hoop op een beter bestaan. De vaas met bloemen staat vreemd genoeg niet binnen,maar buiten in het venster. Ook in de Gouden Eeuw is dat apart, Jan Steen moet er dus iets mee bedoeld hebben. Een boeket staat in het algemeen symbool voor de kwetsbaarheid van het leven. In dit geval verwijst het mogelijk ook naar de dood van de echtgenote van de afgebeelde man.’

Grijzenhout continues: ‘The beggar woman’s clothes are plain, but the fur

on her hat may indicate that she has seen better days. At that time, a hat with

a fur trim was typical German attire. In the 17th century, many poor German

migrants arrived in the rich Dutch Republic in the hope of a better life.

Strangely enough, the vase with flowers is placed not inside, but outside the

window. This is unusual, so Jan Steen doubtless meant something by it. A

bouquet of flowers generally symbolizes the fragility of life. In this case, it

may allude to the death of the husband's wife.’

So the painting depicts a wealthy corn trader who has lost his partner, a well-dressed young girl born into an affluent household, and begging immigrants. The scene is one that one might see in the Netherlands in the present day also, albeit with the characters wearing different clothes. The ‘normal’ Golden Age life depicted by Jan Steen continues to capture the hearts of ‘normal’ people into our current age.

So the painting depicts a wealthy corn trader who has lost his partner, a well-dressed young girl born into an affluent household, and begging immigrants. The scene is one that one might see in the Netherlands in the present day also, albeit with the characters wearing different clothes. The ‘normal’ Golden Age life depicted by Jan Steen continues to capture the hearts of ‘normal’ people into our current age.

TWEE MOMENTEN IN A DIVERS LIFE

TWEE MOMENTEN IN A DIVERS LIFE

There are two moments in a diver’s life:

One, when a beggar, he prepares to plunge;

Then, when a prince, he rises with his prize.

Robert Browning

Robert Browning was a British poet and playwright

active at the start of the nineteenth century. In likening the figure of the

diver making to enter the water as that of a beggar, and in contrast, comparing

his proud form as he surfaces with pearls to that of a prince, Browning clearly

portrays the transformative power of the pearl. Natural pearls were perpetual objects

of desire, thanks to their rarity and beauty. Throughout the 19th century

through to the start of the 20th, Imperial Britain maintained much of the

Arabian Peninsula side of the Persian Gulf, famous for its pearls, as its Protectorate.

The British also harvested pearls from the Gulf of Mannar, between the Tamil

coast of southern India and northern Sri Lanka.

In fact, even before Britain got there, the Netherlands had already been collecting

pearls from the Gulf of Mannar during the Dutch colonial period between 1658

and 1796. Under Dutch control, fishermen would leave pauses in their pearling so

as to give the pearls sufficient time to grow. The pearl oyster has a natural

life cycle of about five years. It has many natural enemies, such as certain

seaweeds and other types of oysters, which hinder its growth. Suddenly, human

exploitation had been added to this list of dangers.

The Gulf of Mannar is home to many large fish

including sharks, and pearl-diving there meant riskng one’s life. The divers would

block their ears and noses, and smear their bodies with oil. They held a basket

either under their left arm or around their neck, tied a stone weighing around

6kg to one foot, and plunged into the sea. Underwater, the divers would attempt

to pick oysters and put them into their baskets as quickly as possible. When

their baskets were full, the divers would tug on their rope and their colleague

in the boat would hurriedly haul them up. The divers took it in turns to go

into the sea, restoring their energy during their breaks. The diving would go

on until evening, when the boat would be loaded with pearls. The boat would

then return with the oysters to the village, and unload its precious cargo. Several

heaps of shells would appear in front of the divers’ cabins by the beach. The

divers would sit around the piles, opening up the shells in search of pearls.

Not all of the shells contained pearls.

After collection, the pearls would be categorized

and appraised by experts known as ‘chitini’. The perfectly round or spherical

pearls were worth the most. Next highest in value were those pearls that were

close to spherical, followed by the oval, pear-shaped and drop-shaped pearls.

The irregularly shaped pearls, known as ‘baroque pearls’, fell into the fourth

category. After the pearls had been classified according to their shape,

weight, lustre, and surface quality, they were sold to traders for high prices.

They were transported by ship to affluent people around the world.

The natural pearl trade declined sharply at the

beginning of the twentieth century. One of the reasons was the rise of Japanese

cultured pearls, as originated by Kōkichi Mikimoto. ‘I shall adorn the necks of

women all around the world with pearls,’ Mikimoto declared. Japanese pearl

farms were able to produce well-shaped pearls in vast quantities, and cultured

pearls cost around a third of the price of natural ones. This development made

pearls accessible to members of the general public for the first time.

Robert Browning was a British poet and playwright active at the start of the nineteenth century. In likening the figure of the diver making to enter the water as that of a beggar, and in contrast, comparing his proud form as he surfaces with pearls to that of a prince, Browning clearly portrays the transformative power of the pearl. Natural pearls were perpetual objects of desire, thanks to their rarity and beauty. Throughout the 19th century through to the start of the 20th, Imperial Britain maintained much of the Arabian Peninsula side of the Persian Gulf, famous for its pearls, as its Protectorate. The British also harvested pearls from the Gulf of Mannar, between the Tamil coast of southern India and northern Sri Lanka.

In fact, even before Britain got there, the Netherlands had already been collecting pearls from the Gulf of Mannar during the Dutch colonial period between 1658 and 1796. Under Dutch control, fishermen would leave pauses in their pearling so as to give the pearls sufficient time to grow. The pearl oyster has a natural life cycle of about five years. It has many natural enemies, such as certain seaweeds and other types of oysters, which hinder its growth. Suddenly, human exploitation had been added to this list of dangers.

The Gulf of Mannar is home to many large fish including sharks, and pearl-diving there meant riskng one’s life. The divers would block their ears and noses, and smear their bodies with oil. They held a basket either under their left arm or around their neck, tied a stone weighing around 6kg to one foot, and plunged into the sea. Underwater, the divers would attempt to pick oysters and put them into their baskets as quickly as possible. When their baskets were full, the divers would tug on their rope and their colleague in the boat would hurriedly haul them up. The divers took it in turns to go into the sea, restoring their energy during their breaks. The diving would go on until evening, when the boat would be loaded with pearls. The boat would then return with the oysters to the village, and unload its precious cargo. Several heaps of shells would appear in front of the divers’ cabins by the beach. The divers would sit around the piles, opening up the shells in search of pearls. Not all of the shells contained pearls.

After collection, the pearls would be categorized and appraised by experts known as ‘chitini’. The perfectly round or spherical pearls were worth the most. Next highest in value were those pearls that were close to spherical, followed by the oval, pear-shaped and drop-shaped pearls. The irregularly shaped pearls, known as ‘baroque pearls’, fell into the fourth category. After the pearls had been classified according to their shape, weight, lustre, and surface quality, they were sold to traders for high prices. They were transported by ship to affluent people around the world.

The natural pearl trade declined sharply at the beginning of the twentieth century. One of the reasons was the rise of Japanese cultured pearls, as originated by Kōkichi Mikimoto. ‘I shall adorn the necks of women all around the world with pearls,’ Mikimoto declared. Japanese pearl farms were able to produce well-shaped pearls in vast quantities, and cultured pearls cost around a third of the price of natural ones. This development made pearls accessible to members of the general public for the first time.

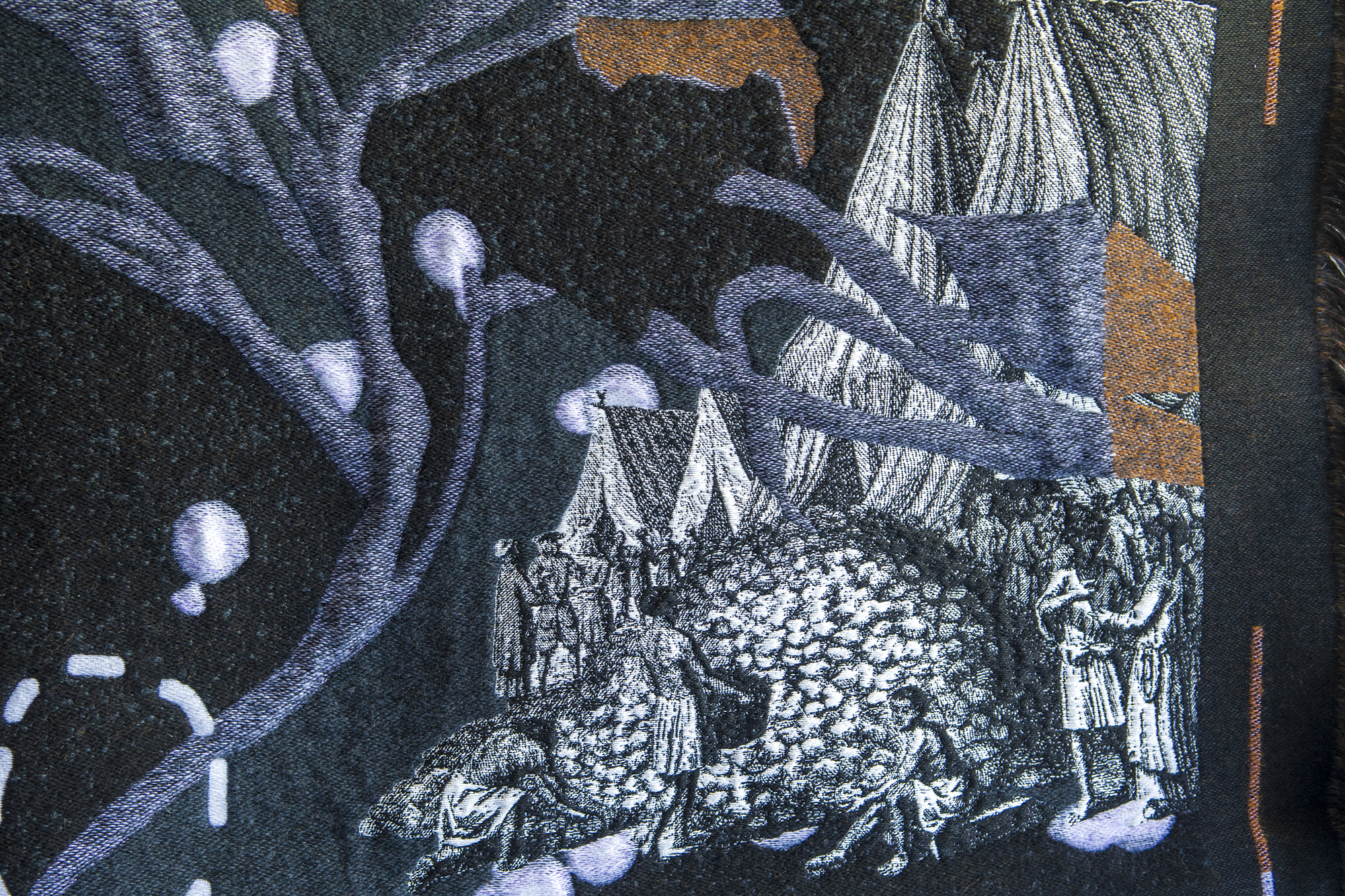

A Diver’s life, Woven Tapestry, hemp and wool; 200 x 140 cm

A Diver’s life, Woven Tapestry, hemp and wool; 200 x 140 cm

OYSTERS FROM OMURA BAY

Omura Bay is located centrally along the coastline of Japan’s Nagasaki

Prefecture, surrounded by lush green mountains. On the eastern side of the bay

is the pearl farm of Noritsugu Matsuda. His workshop sits at the foot of a

small mountain, with the sea stretching out in front of it. Being an inland

sea, its waters are relatively calm. The spot is a peaceful one, with the only

sound being the occasional sound of the trains running along the track circling

the bay.

Pearls from Omura Bay have a long history, and are mentioned in the Hizen-no-kuni Fudoki [A Report on the Culture, Geography and Traditions of the Kingdom of Hizen],

compiled back in the Nara period (710-794). There it

is recorded how, when an ama—female

pearl diver—presented the Emperor with a shell collected in the Omura Bay and

opened it, he was much delighted to see not one but two glimmering pearls

appear. In 1582, towards the end of the Warring States period, the Tenshō emissary

sent by the Christian Daimyo Lord of Kyushu presented a pearl from the Bay of

Omura to Gregory XIII, the Roman Pope at the time.

During the Edo period (1603–1867), it was the

successive generations of feudal lords from Omura clan who protected these

precious natural pearls, and ensured the continued survival of the pearl

fishing industry. They strictly forbade the common people from eating any molluscs.

They were also zealous about the preservation of pearl oysters, and would

periodically impose bans on fishing, during which tiles and stones would be

thrown onto the sea bed to improve the habitat of the pearl oysters. The

monopoly on pearl oysters was an important source of income for the Omura clan,

who exported pearls to the Netherlands via Deshima. Philipp Franz von Siebold,

a doctor who resided on Deshima in Nagasaki, wrote in his book Edo Sanpu Kikō [Account of a Trip to Edo] that powdered pearls were also used as medicine by the Japanese.

This history of natural pearls in Omura Bay which stretches back to

antiquity is linked with the development of cultured pearls. Research into how

to artificially create beautiful pearls was being carried out in various places.

After Kōkichi Mikimoto succeeded in producing a semi-circular pearl in Mie

Prefecture, the first perfectly round pearl was cultivated in Nagashima Island

in Omura Bay, in 1907. The following year, a round pearl was presented to the

Meiji Emperor. Cultured pearls was a Japanese innovation that took the world by

surprise. They were in no way inferior in quality to the natural pearls which

had up until then been so much more expensive.

Matsuda has taken over his family pearl culturing business, along with his

younger brother. The elements of the work that are at sea they always carry out

as a pair, in the case of emergencies. The process of pearl cultivation

consists of: tending to the oysters, seeding the nucleus, and growing and

harvesting the pearls.

Matsuda explains: ‘To produce pearls, you need two kinds of akoya oysters:

a mother oyster and a cell oyster. I buy young pearl oysters—babies, we call

them—and grow them until they are big enough. This is called ‘tailoring’. When I buy them, the shells are

about a millimetre in size, and over the course of two years they grow to about

6 centimetres. There are also pearl farms that don’t buy young pearl oysters,

but grow them themselves from the mother and cell oysters. To culture pearls, you

need to implant the ‘nucleus’ into the mother oyster. This process starts every

year around the end of May, when the oysters are sufficiently large. The

oysters need to be weakened slightly before we insert the nucleus, otherwise

they reject it.’

This process of ‘seeding the nucleus’ means inserting a small section of

the outer shell of the cell oyster and a pearl bead (the nucleus) about 5-7mm

in diameter from a freshwater mollusc to the inside of the mother oyster. The task

is carried out quickly, and looks effortless, but in fact requires a surgeon’s

precision, combining manual instinct and experience.

After this operation, Matsuda leaves the pearl oysters for about ten days

in Omura Bay before transporting them to Kujukushima Island. There, the pearl

oysters spend the cold winter growing. Kujukushima has a stable water

temperature, calm waters, a good tidal current, and abundant plankton. Looking out at the sea, Matsuda says: ‘There

used to be lots of pearl farms in the Omura Bay area. Even here, there were

still about 50 in 1980. But the bay has been polluted by the embankments and

the dams that have been created. When I collect sea cucumbers from the sea

floor, I can see all the rubbish that's flowed into the sea via the river. Our

pearl farm is the only one left on the east side of the bay.’

On Kujukushima, the pearl oysters are cleaned once a week. Unless the

seaweed and other oysters sticking to the shells are thoroughly removed with a

knife, the oysters will die. From the end of November through to the ‘harvest’,

there’s no rest on the pearl farm. The pearls harvested in December are called ‘ichinenmono’

(‘one-year ones’), while those harvested in June the following year are called ‘koshimono’

(‘after the turn of the year ones’). The longer the pearls stay in the sea, the

bigger the pearls can grow, but the likelihood that they will die also increases.

What is needed to create a good pearl? Matsuda answers: ‘Good-quality

seawater, good-quality oysters, tailoring techniques—and luck.' His eyes twinkle

as he speaks. Matsuda views pearl culturing as a job for life: ‘You can work alongside

nature, in a healthy way. The sea is always close by.'

OYSTERS FROM OMURA BAY

Omura Bay is located centrally along the coastline of Japan’s Nagasaki Prefecture, surrounded by lush green mountains. On the eastern side of the bay is the pearl farm of Noritsugu Matsuda. His workshop sits at the foot of a small mountain, with the sea stretching out in front of it. Being an inland sea, its waters are relatively calm. The spot is a peaceful one, with the only sound being the occasional sound of the trains running along the track circling the bay.

Pearls from Omura Bay have a long history, and are mentioned in the Hizen-no-kuni Fudoki [A Report on the Culture, Geography and Traditions of the Kingdom of Hizen], compiled back in the Nara period (710-794). There it is recorded how, when an ama—female pearl diver—presented the Emperor with a shell collected in the Omura Bay and opened it, he was much delighted to see not one but two glimmering pearls appear. In 1582, towards the end of the Warring States period, the Tenshō emissary sent by the Christian Daimyo Lord of Kyushu presented a pearl from the Bay of Omura to Gregory XIII, the Roman Pope at the time.

During the Edo period (1603–1867), it was the successive generations of feudal lords from Omura clan who protected these precious natural pearls, and ensured the continued survival of the pearl fishing industry. They strictly forbade the common people from eating any molluscs. They were also zealous about the preservation of pearl oysters, and would periodically impose bans on fishing, during which tiles and stones would be thrown onto the sea bed to improve the habitat of the pearl oysters. The monopoly on pearl oysters was an important source of income for the Omura clan, who exported pearls to the Netherlands via Deshima. Philipp Franz von Siebold, a doctor who resided on Deshima in Nagasaki, wrote in his book Edo Sanpu Kikō [Account of a Trip to Edo] that powdered pearls were also used as medicine by the Japanese.

This history of natural pearls in Omura Bay which stretches back to antiquity is linked with the development of cultured pearls. Research into how to artificially create beautiful pearls was being carried out in various places. After Kōkichi Mikimoto succeeded in producing a semi-circular pearl in Mie Prefecture, the first perfectly round pearl was cultivated in Nagashima Island in Omura Bay, in 1907. The following year, a round pearl was presented to the Meiji Emperor. Cultured pearls was a Japanese innovation that took the world by surprise. They were in no way inferior in quality to the natural pearls which had up until then been so much more expensive.

Matsuda has taken over his family pearl culturing business, along with his younger brother. The elements of the work that are at sea they always carry out as a pair, in the case of emergencies. The process of pearl cultivation consists of: tending to the oysters, seeding the nucleus, and growing and harvesting the pearls.

Matsuda explains: ‘To produce pearls, you need two kinds of akoya oysters: a mother oyster and a cell oyster. I buy young pearl oysters—babies, we call them—and grow them until they are big enough. This is called ‘tailoring’. When I buy them, the shells are about a millimetre in size, and over the course of two years they grow to about 6 centimetres. There are also pearl farms that don’t buy young pearl oysters, but grow them themselves from the mother and cell oysters. To culture pearls, you need to implant the ‘nucleus’ into the mother oyster. This process starts every year around the end of May, when the oysters are sufficiently large. The oysters need to be weakened slightly before we insert the nucleus, otherwise they reject it.’

This process of ‘seeding the nucleus’ means inserting a small section of the outer shell of the cell oyster and a pearl bead (the nucleus) about 5-7mm in diameter from a freshwater mollusc to the inside of the mother oyster. The task is carried out quickly, and looks effortless, but in fact requires a surgeon’s precision, combining manual instinct and experience.

After this operation, Matsuda leaves the pearl oysters for about ten days in Omura Bay before transporting them to Kujukushima Island. There, the pearl oysters spend the cold winter growing. Kujukushima has a stable water temperature, calm waters, a good tidal current, and abundant plankton. Looking out at the sea, Matsuda says: ‘There used to be lots of pearl farms in the Omura Bay area. Even here, there were still about 50 in 1980. But the bay has been polluted by the embankments and the dams that have been created. When I collect sea cucumbers from the sea floor, I can see all the rubbish that's flowed into the sea via the river. Our pearl farm is the only one left on the east side of the bay.’

On Kujukushima, the pearl oysters are cleaned once a week. Unless the seaweed and other oysters sticking to the shells are thoroughly removed with a knife, the oysters will die. From the end of November through to the ‘harvest’, there’s no rest on the pearl farm. The pearls harvested in December are called ‘ichinenmono’ (‘one-year ones’), while those harvested in June the following year are called ‘koshimono’ (‘after the turn of the year ones’). The longer the pearls stay in the sea, the bigger the pearls can grow, but the likelihood that they will die also increases.

What is needed to create a good pearl? Matsuda answers: ‘Good-quality seawater, good-quality oysters, tailoring techniques—and luck.' His eyes twinkle as he speaks. Matsuda views pearl culturing as a job for life: ‘You can work alongside nature, in a healthy way. The sea is always close by.'

THE HOUSE OF PARELS

Katsuya Fuji commutes every day from his home in Nagasaki City to

Pearlheim, a company in Omura. The area is known for its pearl culturing. Fuji is

the factory manager at Pearlheim. The company name was created by adding the

German word for house, ‘heim’, to the English word for pearl, to mean ‘house of

pearls’. Pearlheim was set up in order to contribute to the independence and

life security of those with severe disabilities, and is the only pearl workshop

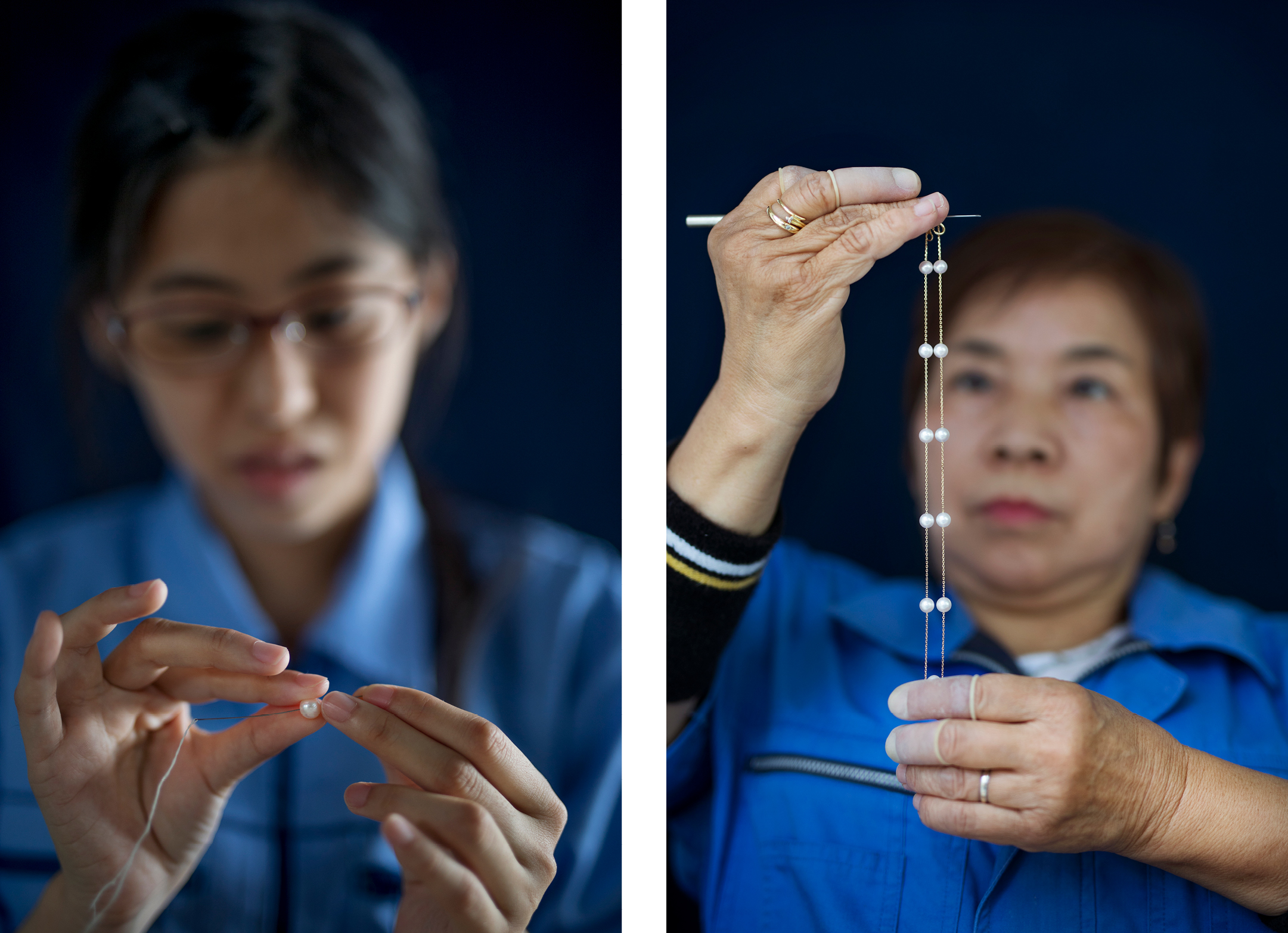

of its kind in Japan. The staff undertake the various tasks necessary to turn

the pearls into jewellery.

Pearlheim was founded in May 1975. It originated when Shunsaku Tasaki,

founder of Tasaki pearl company, was asked by the provincial government to

donate money to the welfare of the disabled.

His response was to suggest establishing a facility where disabled

people could work. ‘The idea is typical of Mr. Tasaki,’ explains Fuji, as he

gives us a tour of Pearlheim. ‘Instead of just donating money, he came up with

a way for disabled people to earn money themselves, and live more

independently.’

‘The working day starts at 8:30 am and finishes at 4:30 pm. After that,

those who live on site have dinner and a bath, and go to bed. The employees

work a half-day on the first and third Saturdays of the month, and the other

Saturdays, as well as Sundays and public holidays, they have off. In their time

off, employees are free to go out drinking or playing pachinko. They have to be

home by 9 pm.’

In the factory, the employees work away in silence. The workspace is very

light and quiet. The expressions on the workers’ faces don't change much. They

are concentrating: on scraping away the excess layer that has formed on the Mabe

pearls; on polishing the nacre layer of the shells; on affixing pearls to

earrings, pendants and rings. Laid out on top of the workbenches, the pearls

sparkle.

‘Pearlheim employs 25 supervisors, and 55 employees with learning difficulties

or physical or mental disabilities. Some commute to Pearlheim on their own,

others have to be picked up, and 28 employees live in the on-site dormitories. It

depends on the person the work they’re doing, but generally, a person’s first

three years at the facility are spent learning how to work, in a way that is

adapted to their particular disability. For example, a task suited to deaf

employees is that of scraping the shell surfaces. It’s a very noisy task, but

it doesn't trouble those with hearing impairments. Other employees can focus well

on one task, but not several at once. We are always thinking about our

employees’ skills and disabilities, so as to put the right person in the right

place.’

Fuji shows us a range of different shells. ‘This is anakoya, this is a South Sea pearl, and this is a black-lip pearl

oyster.... Oh and this is a Mabe. Mabe pearls are produced

differently from other round pearls. They are created with a semicircular nucleus

and are attached to their shell, which generates a semicircular pearl.

Pearlheim works with Mabe shells from Amami Oshima, which have a

rainbow-coloured nacre. Compared to other mother-of-pearl shells, they’re

extremely fine-grained.’

The polished shells change colour depending

on the angle at which they’re held. The mother-of-pearl has a deep lustre. I

remember Fuji's words, ‘the right person in the right place’ again. Where is

the right place for Mr. Fuji, then? ‘Oh, I’m a Jack-of-all-trades,’ he says. As

well as being factory manager, Fuji is also a qualified social welfare worker.

At the company he does all kinds of tasks: driving the bus to collect the

employees, doing admin, polishing shells… Fuji came to work here after a

serious traffic accident 38 years ago: ‘My legs were paralyzed, but then I

realized—the rest of me body can function just like anybody else. That was the

experience that brought me to this job. It’s 32 years now that I’ve been

working at Pearlheim.’

THE HOUSE OF PARELS

Katsuya Fuji commutes every day from his home in Nagasaki City to Pearlheim, a company in Omura. The area is known for its pearl culturing. Fuji is the factory manager at Pearlheim. The company name was created by adding the German word for house, ‘heim’, to the English word for pearl, to mean ‘house of pearls’. Pearlheim was set up in order to contribute to the independence and life security of those with severe disabilities, and is the only pearl workshop of its kind in Japan. The staff undertake the various tasks necessary to turn the pearls into jewellery.

Pearlheim was founded in May 1975. It originated when Shunsaku Tasaki, founder of Tasaki pearl company, was asked by the provincial government to donate money to the welfare of the disabled. His response was to suggest establishing a facility where disabled people could work. ‘The idea is typical of Mr. Tasaki,’ explains Fuji, as he gives us a tour of Pearlheim. ‘Instead of just donating money, he came up with a way for disabled people to earn money themselves, and live more independently.’

‘The working day starts at 8:30 am and finishes at 4:30 pm. After that, those who live on site have dinner and a bath, and go to bed. The employees work a half-day on the first and third Saturdays of the month, and the other Saturdays, as well as Sundays and public holidays, they have off. In their time off, employees are free to go out drinking or playing pachinko. They have to be home by 9 pm.’

In the factory, the employees work away in silence. The workspace is very light and quiet. The expressions on the workers’ faces don't change much. They are concentrating: on scraping away the excess layer that has formed on the Mabe pearls; on polishing the nacre layer of the shells; on affixing pearls to earrings, pendants and rings. Laid out on top of the workbenches, the pearls sparkle.

‘Pearlheim employs 25 supervisors, and 55 employees with learning difficulties or physical or mental disabilities. Some commute to Pearlheim on their own, others have to be picked up, and 28 employees live in the on-site dormitories. It depends on the person the work they’re doing, but generally, a person’s first three years at the facility are spent learning how to work, in a way that is adapted to their particular disability. For example, a task suited to deaf employees is that of scraping the shell surfaces. It’s a very noisy task, but it doesn't trouble those with hearing impairments. Other employees can focus well on one task, but not several at once. We are always thinking about our employees’ skills and disabilities, so as to put the right person in the right place.’

Fuji shows us a range of different shells. ‘This is anakoya, this is a South Sea pearl, and this is a black-lip pearl oyster.... Oh and this is a Mabe. Mabe pearls are produced differently from other round pearls. They are created with a semicircular nucleus and are attached to their shell, which generates a semicircular pearl. Pearlheim works with Mabe shells from Amami Oshima, which have a rainbow-coloured nacre. Compared to other mother-of-pearl shells, they’re extremely fine-grained.’

The polished shells change colour depending on the angle at which they’re held. The mother-of-pearl has a deep lustre. I remember Fuji's words, ‘the right person in the right place’ again. Where is the right place for Mr. Fuji, then? ‘Oh, I’m a Jack-of-all-trades,’ he says. As well as being factory manager, Fuji is also a qualified social welfare worker. At the company he does all kinds of tasks: driving the bus to collect the employees, doing admin, polishing shells… Fuji came to work here after a serious traffic accident 38 years ago: ‘My legs were paralyzed, but then I realized—the rest of me body can function just like anybody else. That was the experience that brought me to this job. It’s 32 years now that I’ve been working at Pearlheim.’

Katsuya Fuji commutes every day from his home in Nagasaki City to Pearlheim, a company in Omura. The area is known for its pearl culturing. Fuji is the factory manager at Pearlheim. The company name was created by adding the German word for house, ‘heim’, to the English word for pearl, to mean ‘house of pearls’. Pearlheim was set up in order to contribute to the independence and life security of those with severe disabilities, and is the only pearl workshop of its kind in Japan. The staff undertake the various tasks necessary to turn the pearls into jewellery.

Pearlheim was founded in May 1975. It originated when Shunsaku Tasaki, founder of Tasaki pearl company, was asked by the provincial government to donate money to the welfare of the disabled. His response was to suggest establishing a facility where disabled people could work. ‘The idea is typical of Mr. Tasaki,’ explains Fuji, as he gives us a tour of Pearlheim. ‘Instead of just donating money, he came up with a way for disabled people to earn money themselves, and live more independently.’

‘The working day starts at 8:30 am and finishes at 4:30 pm. After that, those who live on site have dinner and a bath, and go to bed. The employees work a half-day on the first and third Saturdays of the month, and the other Saturdays, as well as Sundays and public holidays, they have off. In their time off, employees are free to go out drinking or playing pachinko. They have to be home by 9 pm.’

In the factory, the employees work away in silence. The workspace is very light and quiet. The expressions on the workers’ faces don't change much. They are concentrating: on scraping away the excess layer that has formed on the Mabe pearls; on polishing the nacre layer of the shells; on affixing pearls to earrings, pendants and rings. Laid out on top of the workbenches, the pearls sparkle.

‘Pearlheim employs 25 supervisors, and 55 employees with learning difficulties or physical or mental disabilities. Some commute to Pearlheim on their own, others have to be picked up, and 28 employees live in the on-site dormitories. It depends on the person the work they’re doing, but generally, a person’s first three years at the facility are spent learning how to work, in a way that is adapted to their particular disability. For example, a task suited to deaf employees is that of scraping the shell surfaces. It’s a very noisy task, but it doesn't trouble those with hearing impairments. Other employees can focus well on one task, but not several at once. We are always thinking about our employees’ skills and disabilities, so as to put the right person in the right place.’

Fuji shows us a range of different shells. ‘This is anakoya, this is a South Sea pearl, and this is a black-lip pearl oyster.... Oh and this is a Mabe. Mabe pearls are produced differently from other round pearls. They are created with a semicircular nucleus and are attached to their shell, which generates a semicircular pearl. Pearlheim works with Mabe shells from Amami Oshima, which have a rainbow-coloured nacre. Compared to other mother-of-pearl shells, they’re extremely fine-grained.’

The polished shells change colour depending on the angle at which they’re held. The mother-of-pearl has a deep lustre. I remember Fuji's words, ‘the right person in the right place’ again. Where is the right place for Mr. Fuji, then? ‘Oh, I’m a Jack-of-all-trades,’ he says. As well as being factory manager, Fuji is also a qualified social welfare worker. At the company he does all kinds of tasks: driving the bus to collect the employees, doing admin, polishing shells… Fuji came to work here after a serious traffic accident 38 years ago: ‘My legs were paralyzed, but then I realized—the rest of me body can function just like anybody else. That was the experience that brought me to this job. It’s 32 years now that I’ve been working at Pearlheim.’