Remodeling Shiseido Gallery Edition

2021Remodeling Shiseido Gallery Edition is a work by Anneke Hymmen and Kumi Hiroi commissioned by the Shiseido gallery in Tokyo Japan for the exhibition: Anneke Hymmen & Kumi Hiroi, Tokuko Ushioda, Mari Katayama, Maiko Haruki, Mayumi Hosokura, and Your Perspectives. By using the same concept of Remodeling that Hymmen and Hiroi have started in 2014, they created Remodeling Shiseido Gallery Edition based on the two advertisements of Shiseido.

Mika Itagaki, the curator of the Shiseido Gallery asked visitors of the gallery to describe in words two Shiseido advertisements. The collected words became their working material. Without seeing the original advertisements they reconstructed their own visual interpretations of the descriptions at hand. The resulting images are four portrait photos. They chose two photos and asked Akiko Otake to write two stories using their photos as inspiration for short stories.

Links: Shiseido Gallery

Concept: Anneke Hymmen & Kumi Hiroi Research and Development: Kumi Hiroi Photo: Hymmen & Hiroi Text: Akiko Otake Translation: Polly Barton

Curator: Mika Itagaki Supported by Dutch Creative Industry Fund

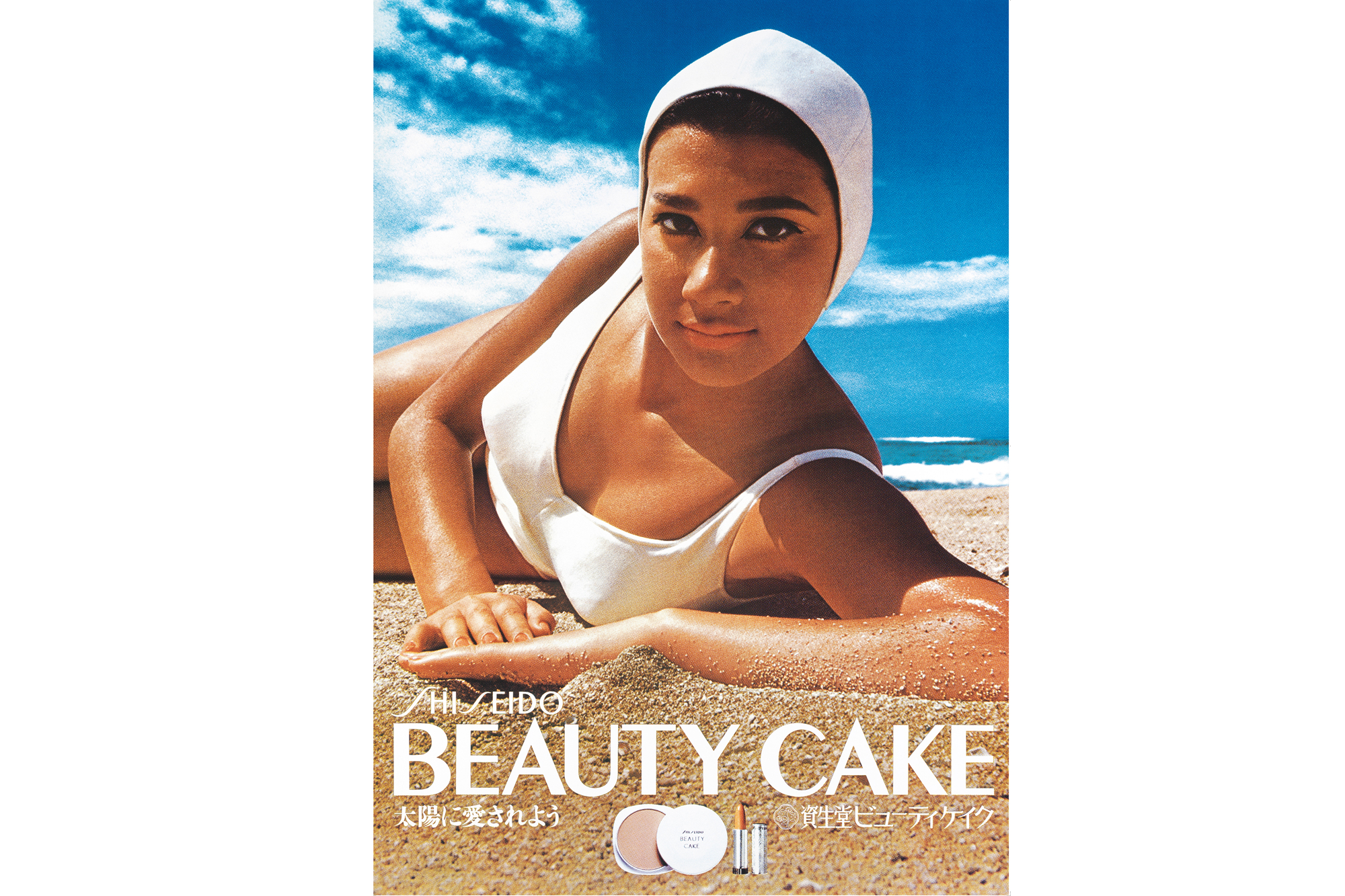

Shiseido Beauty Cake “Beloved by the Sun” Poster,1966 Photo: Noriaki Yokosuka, Model: Beverly Maeda ©Shiseido

Shiseido Beauty Cake “Beloved by the Sun” Poster,1966 Photo: Noriaki Yokosuka, Model: Beverly Maeda ©Shiseido

K: These words transport me to a beach. This is quite a classic scene, no?

A : In the Netherlands, there’s only a limited number of days where we could shoot this on location, though. We’re not famous for our sunny weather... What do you mean by a classic scene?

K: With words like blue sky, dazzling sunlight, and white swimsuit, the first thing that comes to my mind is a Mediterranean summer scene. Although I’m not a beach person really. I’ve never lived near to the sea, and I don’t have a strong connection to it. So I guess the first image I imagine is the generic Mediterranean beach, rather than something from my personal experience.

A:You mean those images that you see a lot in travel advertisements or TV commercials? Models jumping on a white sand beach or people drinking cocktails and so on?

K: Yes. Sometimes, although I don’t look at Instagram and other social media that often, I can look at a professionally taken image there and perceive it, unconsciously, as just a regular photo. And then I process that image as a standard image. In the way that I had the Mediterranean Sea in my head, even though I wasn’t familiar with it.

A: Yes. I think the same when I show my clients sample photos to represent ideas for future jobs. You know when you have meetings with them, right? I make several versions because I want to show a variety of different directions we could go in, and I notice that stock photos go down well with clients. Even though it’s clear that when you actually shoot a scene like that in real life, it will look different, right? The models are heavily photoshopped as well, in those sorts of images.

The photos that are eventually delivered have a strong documentary element, and the clients seem to be happy with that. So why do you think people think that stock photos are realistic?

K: I guess whatever you’re used to seeing becomes reality in your mind. Even if that’s not the reality.

A: Returning to the Summer, heat, light, dazzling sunlight...’, what shall we do about white clouds? If there aren’t any white clouds that day, should we Photoshop them in later?

K: I don’t know… I have a feeling that it’s not a good idea to Photoshop them in. But if there are no white clouds on the date of the shoot, I guess we have to consider it.

A: Yes.

K: The image composition that came to my mind first was like the photo of Niels that we took for Ping Pong. The face and torso are in focus and the background is blurred. But instead of the pink/light blue gradated background of the sea, we’d have the blue sky and sun.

A: Yes. The sun is strong and there’s sandy sweat on the model’s skin.

K: Who could be the model?

A: The description doesn’t mention anything about the model. It could be anyone. I’d prefer not to use a typical female model. A typical model in combination with summer, blue sky, and a white swimsuit could look clichéd.

K: What do you mean by a typical model?

A: You know what I mean. Someone with very long thin legs and arms and a symmetrical face. Isn’t it strange that there is no description of the model? There must be one in this advert.

K: That’s true, there are no words written about the model. It’s a Shiseido summer advertisement, so it might be a sunscreen advertisement.

Behind the Eyelids

That day, after returning from the beach, I ate a quick breakfast and then entered my studio right away. I set the primed canvas onto the easel, and dipped a fine brush into brown paint that I’d thinned down considerably. Beginning with the forehead, I moved the brush in one fluid line, tracing the hollow of the eye socket, the pointed tip of the nose, the mouth, then lifting from the chin up to the ear before drawing in the curve of the neck. With the addition of one more line running in parallel, the outline of the head was established.

Almost immediately after getting up that morning I’d set out for the beach, which lay about twenty minutes’ walk away from my house. As always, my camera hung from my neck. Standing on the strip of sand from which the morning tide had began to recede, I raised the finder to my eye and began moving the camera back and forth, side to side, in search of something that piqued my interest. The task I set myself is to look carefully, to remember, and then to paint what I see. I use a telephoto lens in order to better remember whatever I look at. I find it hard to get my imagination working by taking things in hand, or moving close enough towards them that I can physically sense their distance. Rather, I like to quash the usual sense of distance, the standard relationship we have with objects when looking at them, and to generate instead an image that appears somewhere severed from an everyday context. For that purpose, I find a 100mm telephoto lens works well. As soon as my eye meets the finder, the distance vanishes, and I’m drawn inside a different way of seeing. Do you actually press the shutter? I’m often asked, and my answer is no. Commit the scene to a photograph and it becomes a memory of the eyes, filtered through the camera. What I want to paint is rather the world that materializes on the other side of the lens, set apart from my physical being.

In the frame that morning was a woman facing out to sea, shown from the chest up. Her long hair, pushed up from her forehead. hung down her back; her chin was slightly raised, and her eyes were closed. Keeping the lens trained on her face, I used my eyes to trace the contours of her forehead, her nose, her mouth, her chin. Her neck was impressively long, and seemed to burst forward diagonally from her shoulders. There was something about her sculptural form, its proportions slightly exaggerated, which I found myself drawn to.

In the studio, I worked for five hours in a state of absorption, breaking only for lunch, and then my hand came suddenly to a halt, as if I’d run out of gas. The canvas before me was layered with light browns, ochres, and beiges. As I’d repeatedly gone over the outlines, the figure I was depicting had blended with its background—to such an extent, in fact, that one couldn’t tell any more that the canvas depicted a person. I didn’t want to explain the woman, but rather to bring into focus her true essence. So what was that true essence, then? The only reply I could have given to such a question would was that it was something that transcended form. 'Trying to capture a person's true way of being which transcended form’—putting it into those words, it made little sense, but it was exactly that paradox that I wanted to enact in my artwork.

I’d been invited for dinner that evening at the house of a friend who lived in the next town along. An acquaintance of theirs from Japan was coming to stay, and the friend had announced the intention to make sushi. The idea of sushi appealed, but part of me was resistant. I wanted to remain immersed in the woman’s image for longer. It seemed that if I pulled myself away, then what I had achieved today would slip away from my eyes. Yet I decided to go to my friend’s regardless. I’d cancelled our last meeting after something sudden had come up, and I felt reluctant to do so again.

As it turned out, I may as well have cancelled. On the drive to my friend’s house I had a car accident, and never made it there. According to the police’s explanation afterwards, I’d turned too soon coming right off the bridge, and smashed into the railing. When I regained consciousness, I had no memory of the incident at all. Staring up at the unfamiliar ceiling floating above me, I wondered where on earth I was.

My body was exhaustively examined using all kinds of devices, from the top of my head down to my toes, but the doctors could find nothing out of the ordinary. They had no explanation of why I might have caused an accident of that kind. The parts of myself I’d hit upon collision were a little sore, but that was the extent of my injuries, and I was amazed to discover that I had no visible wounds. On the fourth day I was told there was no need for me to stay any longer, and discharged.

Reaching home, I headed straight into my studio, and came to a stop in front of my easel. The sight of the painting I’d begun that day leapt out at me. There was no doubting it. It was the same person—the first nurse who’d come to see me after I’d regained consciousness. As my eyes had fallen on the long neck protruding from the triangular collar of her uniform, I’d been taken by the feeling that I’d met her somewhere before. The second time she came to my bedside, that sense became a conviction, and so I asked her. “Were you on ------ beach early Friday morning?” She cocked that long neck of hers, and then answered, ‘No, that couldn’t have been me. I was on the nightshift, and fell asleep immediately after. I woke up after 2pm.’

Maybe her memory was mistaken, I thought. But no, that wasn’t it. Recalling the way her closed eyes looked that morning on the beach, I suddenly understood. They were the eyes of a person who had climbed out of bed in the middle of sleep—a person watching whatever images flicked across the underside of her eyelids. I had been taken along on those eyes’ voyage, and finally, now, I had returned. As this idea moved into the realm of certainty, I felt the strength brimming up in me. I threw off my coat, picked up my brush, and carefully lowered it onto the canvas.

Short story by Akiko Otake, Translated by Polly Barton

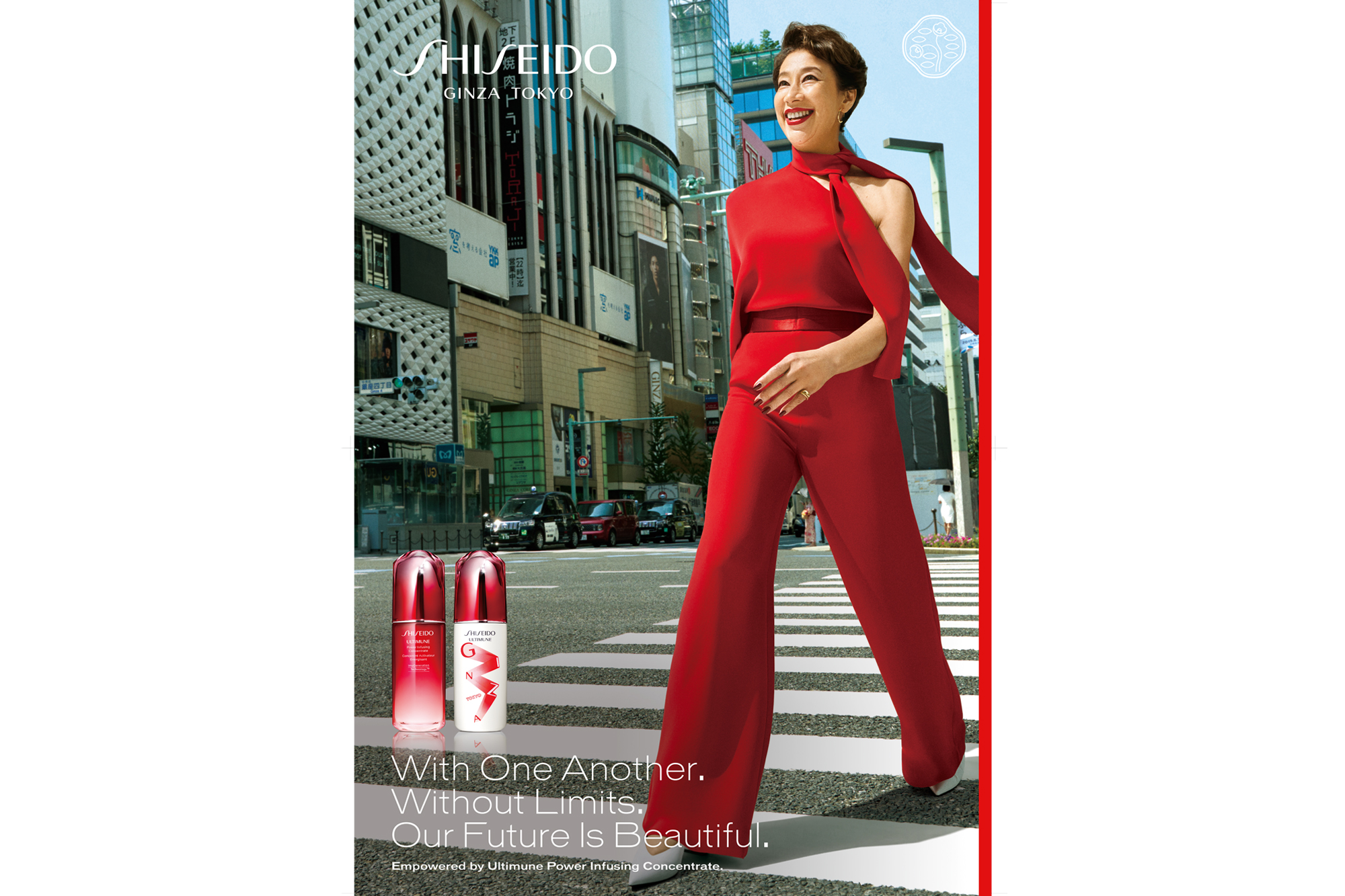

SHISEIDO Ultimune “With One Another. Without Limits. Our Future Is Beautiful.”, Poster, 2020

Photo: Sebastian Kim, Model: Beverly Maeda ©Shiseido

Photo: Sebastian Kim, Model: Beverly Maeda ©Shiseido

K: What do you think of this description? Do you have any particular associations with any of these words?

A: Well, in the context of Amsterdam, pride makes me think of Gay Pride. What do you think?

K: You’re right, the English word ‘pride’ has become associated with ‘Gay Pride’ here. Also ‘Transsexual pride’, and ‘Women with pride’. It’s used for people who feel their rights aren’t treated equally. In Japanese, the English word pride often has a negative meaning, such as “having a lot of pride” or “wounding pride”, but originally the word is about honouring and having respect for oneself. The Gay Pride flag is a rainbow. I think that’s also a symbol of respect for individuality and diversity. What about the other words? passion, progress, and so on…

A: Well, for me, passion lies in the energy of the model. You feel it through a person’s body language and the expression of their eyes. So, we can think about body language. How do you show passion with body language?

K: The model looks straight into the camera.

A: But if you capture someone standing in a strong posture looking away from the camera, that might also look passionate.

K: That’s true. Then how about the pose? What is a ‘passionate pose’?

A: I think people sitting on a chair with their legs spread expresses a certain strength. Also open arms signify passion. Feet on the ground also says strength? And then in terms of the opposite, covering the face with hair, or putting hands in front of your face reduces a sense of both passion and strength.

K: How about progress?

A: The photo could be a frozen moment from a particular movement. A moment cut out from a process. We’ve got the word healthy, so we could think about a sporting situation.

K: Yeah. Who could be a model?

A: I can imagine Mariko or Salome working well?

K: Good idea. Both have a strong look, and at the same time give a calm and confident impression. Both have black hair. Salome has dark skin and curly hair. Mariko has western features, and her hair is straight.

A: Huh? That is funny. For me as a German, with her almond eyes and black straight hair, Mariko looks Asian. Also her cheekbones I guess make her Asian-looking for me. For you as a Japanese person, she has western features. Interesting.

K: I guess we hold things up to our social and cultural background. For better or for worse, that influences the way we look at people.